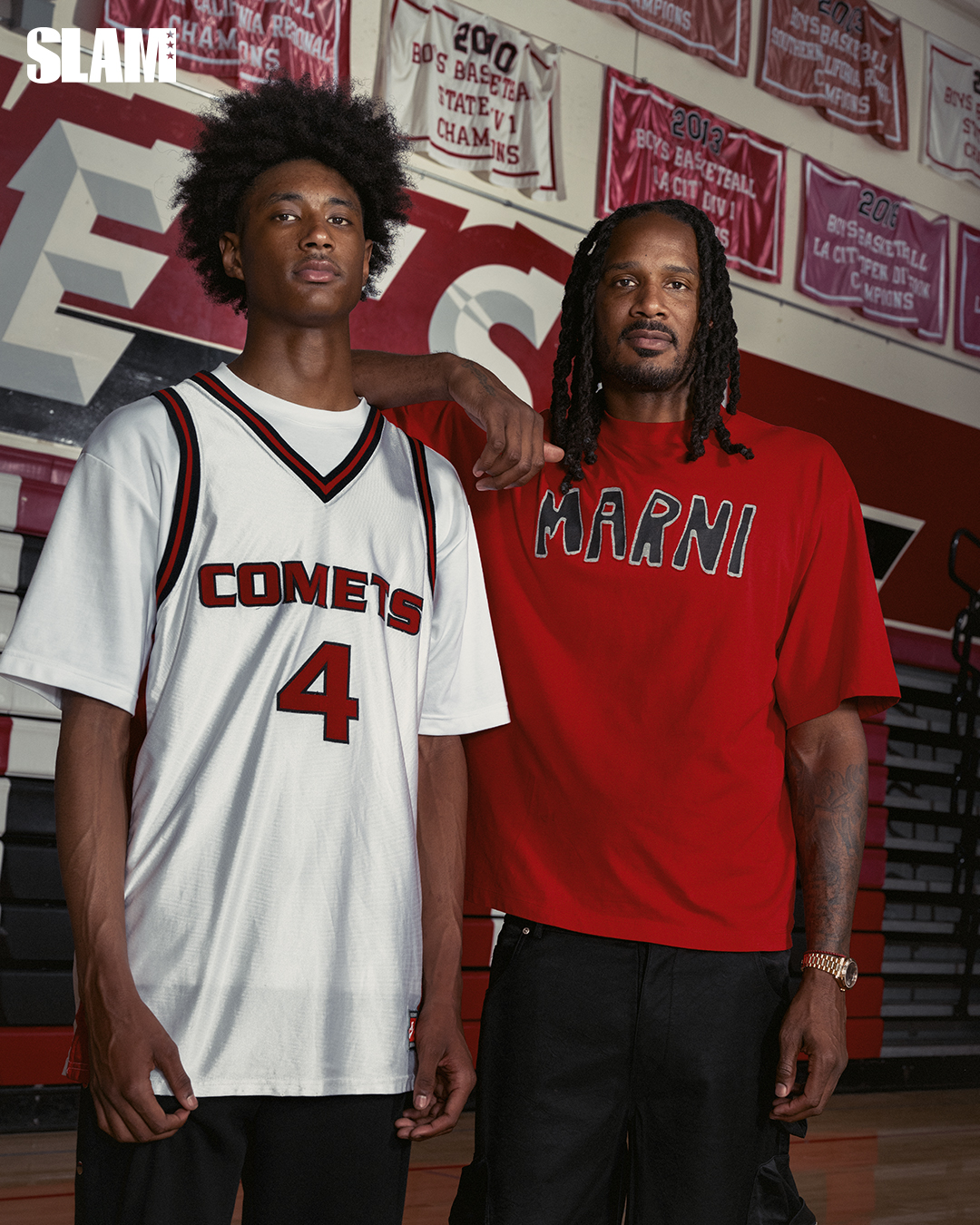

Tajh Ariza Talks About Transferring To His Father's Alma Mater And Taking On The Family Name

The first time Trevor Ariza realized his son was different was at a fourth-grade basketball game. After breaking the poor 8-year-old in one move, Tajh Ariza drove the paint and kicked the rock to an open shooter with a seamless pass behind the backcourt. “The timing was perfect. It was fast. It was a perfect pass,” said Trevor.

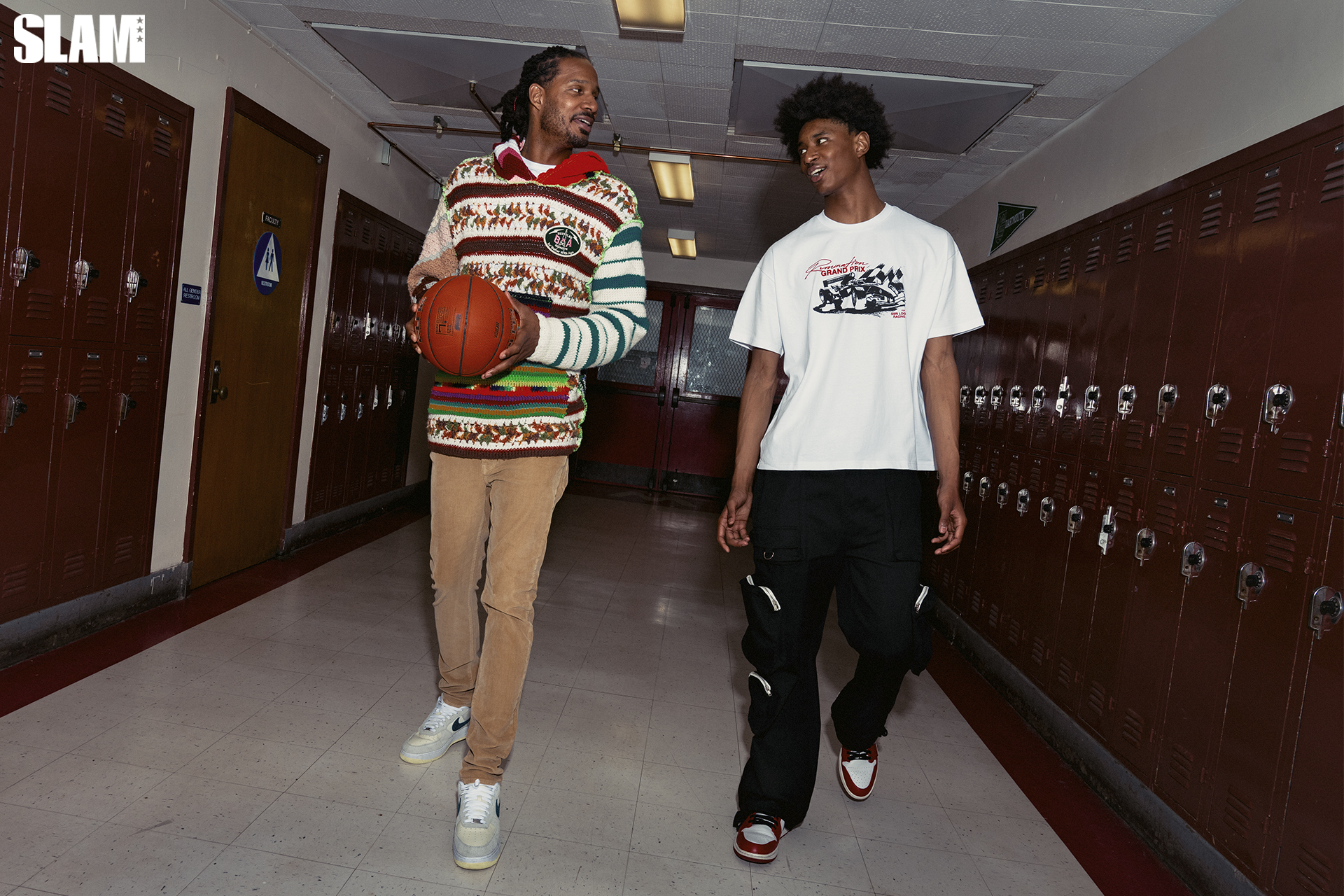

It's a typical sunny day on the west side of LA and Trevor, Tajh and Tristan Ariza are trying to see who can hit a court shot first. It's been two years since the NBA champion and LA native retired, and today, he's back at the center where his basketball reign began. Except for Trevor, he's not in the old white, red and black stripes. His eldest son, Tajh.

Tajh is currently one of the top 16-year-olds in the nation, and come next fall, he will be running on the same field as his father. After finishing the basketball season at St. Bernard HS, Tajh soon after transferred to Westchester this spring.

Inside the school's gymnasium, Tajh stands in a courtyard surrounded by a sea of red, black and white, from the bleachers and walls emblazoned with “Comets” to the shadows of his father's No. 4 home jersey. Faded banners displaying Trevor and the Comets' bi-district titles hang proudly as father and son play by play. Even now, Trevor's influence remains. He has been surrounded by Tajh since he was a kid, playing with Kobe and Derek Fisher. Yes, he is the son of an NBA player. But Tajh Ariza's game is completely his own.

“I have to keep working every day,” said Tajh. “You know, father [had a] good job, but I want to have my own name and show people like, Oh, I want to be like him, do you know So I have to keep working to get there.”

The rising 6-8 junior burst into the recruiting cycle and is now considered a top-10 pick in the 2026 class. After his freshman year, he held three major DI offers. In five months last year, he accumulated another five. This past spring he received an invitation to the USA Junior National Minicamps, and this summer he played with Team Why Not 17U on the EYBL circuit. Things are just clickin'.

But the path was not laid out easily. Trevor allowed Tajh to discover his own passion for the sport. He did not push, he did not move; he sat down and watched his son find the love they had now.

“My opinion of him was always good before he got to high school, if he was serious about it, I would give him all the tools I use or things I learned to help him. “So I would say that if he was serious—about wanting to get better or actually work in basketball—he would be in ninth grade,” Trevor said.

Tajh agrees. He loved the game, but there's a big difference between loving the game and loving something enough to commit to working 5 a.m., two days and a grueling 82-game season.

“I had to change my habits. Before maybe middle school, I didn't really take it seriously. It was just fun for me I guess. Yes, it's still fun,” said Tajh, “but now I see that I have a real chance at what I want to do and be great. And I just kept going. I just took it.

Just before Tajh entered his freshman year, Trevor laid out what it would look like for his son to reach his full potential. It concludes with a gentle but subtle reminder: It's time to kick it into the next gear. “I sat down with him and told him that it won't be fun. Most of the time, it won't be easy. It will take a lot of sacrifice. And many children, when they feel they have to sacrifice or deprive themselves of fun or free time, they become ashamed of things. Luckily for me, he wanted to do it. So it was easy,” said Trevor.

In the year since, Tajh and Trevor have created a dedicated program. At least three times a week before school, they lift or sand drill with Trevor's old Hoop Masters teammate. Working on the soft sand of LA's beaches is taxing, exhausting, sad—all of the above. But his explosion has begun. Tajh says: “I started tricking people, that's why I saw that it started to help.” Off the court, he learns how big guards like Paul George and Brandon Miller create space.

After a shower, breakfast and school, Tajh will hit whatever schedule he didn't make in the morning before heading to the court for a bunch of shooting and ball-handling drills. From the gym to the sand dunes, Trevor is there with his son.

Tajh's dedication is persistent, a combination of recognizing the professional aspects of his father's work and a desire to carve out his legacy. Getting up at 5:30 a.m. to run in the ever-changing sand is as much mental exercise as it is physical exercise. While Tajh welcomes the results of his work, Trevor sees it as a mile marker for how far his son has come since their New Year's conversation.

“It's easy, for him especially since he's so young, to get the attention he's getting, like, relax and hang on to that. And my message to him is just put your head down and focus on the job you're doing,” said Trevor. “Focus on the hours you put in in the gym, on the sand, watching the game, studying the game, focus on that. Everything else will take care of itself.”

When he moved from North Carolina to LA to attend Saint Bernard HS as a sophomore, Tajh says the talk about his game was quiet except for the lure of his last name. That was until early in the season when he received his first two offers from the University of Washington and USC. He still has the reaction video on his phone. “I was very happy. I was jumping on the ground, screaming. It felt good to finally get, you know, what I felt like I deserved. But it also motivated me to keep going. [To] just keep piling on that,” said Tajh.

Proving that happiness to his relatives is a pride only a parent can have. At the same time, Trevor has reduced his advice even after 18 years of playing in the L with the 2009 champion Lakers and left with 10 different organizations. The guidance he gives his sons is often based on the steps he took on his journey to the NBA. And since their games are different, so are the options and decisions available to them.

As Tajh prepares to enter his junior season and his younger brother, Tristan, prepares to start school, too, Trevor knows he can't take on the role of coach, father and teacher at the same time. He should choose and be careful about the hats he wears, and when he wears them.

“If there's a week where I'm having a hard time, like, Clean your room or Take out the trash. How many times do I have to tell you to take out the trash? I have to be comfortable with what happened in court, because I have a hard time with them at home,” said Trevor.

When Tajh takes care of business at home, Trevor will give up some information. “But then again, it's his sail. So he has to paint it the way he sees it. I can only fix small things or give him small nuggets until he comes to me for big things.”

Big things like transferring to your dad's alma mater.

As he looks up at the banners his father put up decades ago, Tajh feels the pain on his back grow. Teachers have already reminded him of the school's legendary past battles with crosstown rival Fairfax. But noise is just that: noise. And as her father walks down the halls where she lived, she knows that Tajh is absolutely ready to enter hers.

“I think with Tajh, he has always been there. So, it's almost like second nature,” Trevor said. “He can walk on his own as he can talk. It was made for him. Some children are born to do certain things. And to me, in my eyes, I feel like he's one of those babies that was just born to be in this space.”

Photos by Sam Muller.

! function(f, b, e, v, n, t, s) {

if (f.fbq) return;

n = f.fbq = function() {

n.callMethod ?

n.callMethod.apply(n, arguments) : n.queue.push(arguments)

};

if (!f._fbq) f._fbq = n;

n.push = n;

n.loaded = !0;

n.version = ‘2.0’;

n.queue = [];

t = b.createElement(e);

t.async = !0;

t.src = v;

s = b.getElementsByTagName(e)[0];

s.parentNode.insertBefore(t, s)

}(window, document, ‘script’,

‘

fbq(‘init’, ‘166515104100547’);

fbq(‘track’, ‘PageView’);

Source link